I first was introduced to Fernando Pessoa through his famous collection of fragments, The Book of Disquiet in my MFA program by my mentor, Garrett Hongo. I believe it was for a course on memoir. Since then, through many moves, I’ve kept my heavily marked-up copy for 30 years, but only now, after a recent trip to Lisbon, is it out on my desk again.

Pessoa is an enigma who created at least 72 different heteronyms complete with different professions, countries, time periods, and astrological charts. In Richard Zenith’s biography, Pessoa, he documents just one female heteronym, Maria Jose.

“A nineteen year old hunchback who suffered from tuberculosis and crippling arthritis, Maria Jose spent her days next to a second floor window and felt her heart flutter each time Senhor Antonio, a handsome metal worker, passed by on his way to or from work. While she had no intention of sending it, she wrote him a long and poignant letter, dating from 1929 or 1930” (Zenith xi).

What fascinates me about heteronyms (a word Pessoa invented) is that they are not pseudonyms but fully realized characters or as Pessoa states, “my non-existing acquaintances” or “my collaborators.” The poetic styles vary greatly. Some write in English and are down and out or aristocratic; others write only of the natural world. Imagine a poet with multiple personality disorder; each personality, a poet.

Pessoa knew of Whitman’s “I contain multitudes” and took the concept further. In Portuguese, “pessoa” is also the word for person. In this time of identity politics, it’s especially freeing to move beyond the single self.

Fernando Pessoa, painted by his friend, the artist Jose de Almada-Negreiros

At one time, Pessoa undertook a study of his family tree, looking into the madness of different relatives (one grandmother, one aunt) as a kind of proof that he was predisposed to be a genius. The different imaginary people he invented began with his childhood friend, “Chevalier de Pas” or “The Knight of Nothing.”

“When I consider, with all the clarity I can muster, what my life has apparently been, I imagine it as some brightly colored scrap of litter — a chocolate wrapper or a cigar ring — that the eavesdropping waitress brushes lightly from the soiled tablecloth into the dustpan, among the crumbs and crusts of reality itself.”

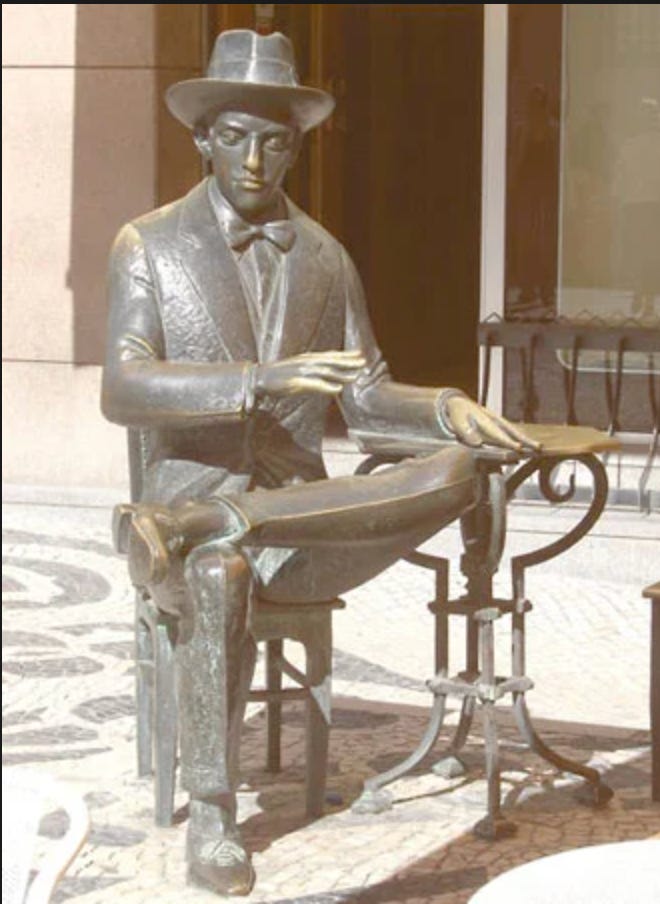

Today, the entire city seems to be honoring Fernando Pessoa, everywhere I went there was a plaque (he had lived on the street where I stayed; he lived on many streets) or a statue sitting outside a bar, or a world class museum. The bookstores I visited were filled with his poetry and prose. Even the café bar where Pessoa frequented, A. Brasiliaria, has published a collection of his work, Message, in a special edition available in Portuguese, English, French, Spanish, Italian, and Mandarin.

In other words, this guy has a strong following almost 90 years after his death. His biographer, Richard Zenith, places him among the most important 20th century writers alongside James Joyce and Marcel Proust.

The Fernando Pessoa House in Lisbon has recently been voted the best museum in Europe. I understand why. As I entered the exhibition space, I heard the familiar sound of typewriter keys and at the same time, saw Pessoa’s red typewriter floating in space. There are recordings of Pessoa’s poems in Portugese and in English as well as his letters to his one known girlfriend.

“To read is to dream, guided by someone else’s hand.”

Statue of Fernando Pessoa outside the A. Brasiliaria cafe that he often frequented. I also visited there often for the best coffee and delicious pastel de natta.

“I am the suburb of a non-existent town, the prolix commentary on a book never written. I am nobody, nobody. I am a character in a novel which remains to be written, and I float, aerial, scattered without ever having been, among the dreams of a creature who did not know how to finish me off.”

Pessoa from The Book of Disquiet

The next week is a full celebration of the city of Lisbon with all of its 20 neighborhoods taking part in parades (with floats), partying, and revelry. How absolutely right that this is also the week Pessoa was born into the world. I leave you with one of my favorite poems of Pessoa’s, “The Tobacco Shop.”

Here is how it opens —- as if he is perhaps channeling Emily Dickinson:

The Tobacco Shop

I'm nothing.

I'll always be nothing.

I can't want to be something.

But I have in me all the dreams of the world.

Windows of my room,

The room of one of the world's millions nobody knows

(And if they knew me, what would they know?),

You open onto the mystery of a street continually crossed by people,

A street inaccessible to any and every thought,

Real, impossibly real, certain, unknowingly certain,

With the mystery of things beneath the stones and beings,

With death making the walls damp and the hair of men white,

With Destiny driving the wagon of everything down the road of nothing.