Back and Forth on the Ferry with Millay-Keeping It Real

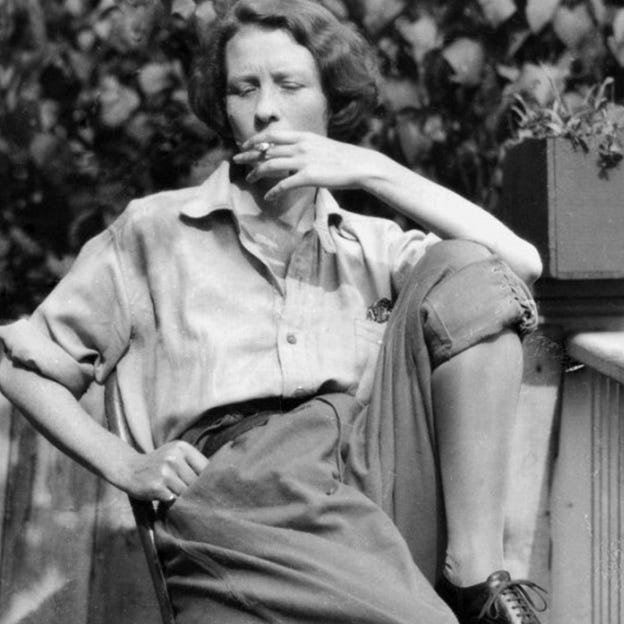

True Stories of the Cultural Icon Edna St Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay was my first true poetry love. Readers, I hardly knew her.

Reader, I wonder what drew me to this versatile, political, and ultimately tragic poet when I was nine years old? That’s 4th grade for the non-USA readers.

Actually, I am pretty sure I know. Can you guess? It was all those imperfectly perfect love sonnets. I can remember the cover of the paperback so clearly, a dove-blue background with The Sonnets in gold script. I hid the book in my closet. What was I afraid of, I wonder?

Nine years old. Finally allowed to walk to the library by myself—or with my friend Jennifer. Nine years old—what did I know of love? Maybe this was the beginning of having crushes? The first flush of —can a 9 year old feel desire? Well, she can imagine it.

I didn’t know that Millay was famous for having many, many lovers. I didn’t know that she moved one young lover (she met him when she came to read at the university where he was a student) into her home in Austerlitz, New York, to live with her and her husband. I didn’t know that she had a made to order gun collection (like jewelry, only not) or that she was an alcoholic. I didn’t know that her mother helped her abort a fetus so that she could attend college.

Of course, in the 1960’s, none of this was common knowledge. I once met an old, elegant, Russian woman who had immigrated to Wellesley, Massachusetts. It was a summer party, a friend of a friend of a friend kind of thing. Perhaps I told her I wrote poetry, perhaps not. But somehow the subject of Edna St. Vincent Millay had come up. Thirty-plus years later I can still see her eyes, piercing with the force of her diamond and gold rings.

“You cannot compare her to anyone writing today. Think Madonna,” she’d said. A poet as big as Madonna in the late 1980’s? Today it would be: Think Taylor Swift or, Think Beyoncé.

It wasn’t until the biography Savage Beauty The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay came out, that the average human (reader, that’s me) came to know anything of Millay’’s life: her steel ambition, her family’s poverty, or her queerness. Of course, even in 2001, bisexuality was not yet mentioned, although as a young woman living in New York, she dated men and women, the biography makes no mention of it.

But none of that mattered to me. Her poems were openly feminist for their time and the sense of a different kind of life was evident in everything she wrote. When, later I discovered that she was a political activist writing a poem openly against the death penalty. She was a self-proclaimed Anarchist and her collected letters show her behind the scenes work to try and save Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian immigrant workers that were charged with murder and robbery, but were widely believed to be innocent. Later, “Vincent” would be an active pacifist during World War 1 and World War II — some believe leading to the demise of her career.

Edna St. Vincent Millay was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. The first writers residency I ever attended was her Sears Roebuck barn in Austerlitz, New York in the winter of 99 inches of snow. (This is also where Mary Oliver worked for Vincent’s sister Norma just after Oliver left high school.)

She remains one of my poetry foremothers although best pal to go partying with might describe her more accurately.

“Oh, Oh, You Will Be Sorry for that Word”

Oh, oh, you will be sorry for that word!

Give back my book and take my kiss instead.

Was it my enemy or my friend I heard,

“What a big book for such a little head!”

Come, I will show you now my newest hat,

And you may watch me purse my mouth and prink!

Oh, I shall love you still, and all of that.

I never again shall tell you what I think.

I shall be sweet and crafty, soft and sly;

You will not catch me reading any more:

I shall be called a wife to pattern by;

And some day when you knock and push the door,

Some sane day, not too bright and not too stormy,

I shall be gone, and you may whistle for me.