Living in the Boston area in the 1970’s, 1980’s, and early 1990’s meant being only one degree removed from some of the greatest American poets of the late 20th century. I didn’t “know” Seamus Heaney (but he did live across the street from me and I saw him frequently toting his dry cleaning). I didn’t ”know” Derek Walcott (although he was my close friend’s professor at B.U.) But as an aspiring poet-to-be, I did pay attention.

In high school I worked a number of different jobs at flower shops and plant stores. For awhile, I considered majoring in horticulture. So many lives we never get to lead... I thought a life of poetry and plants sounded like a good idea. I still do.

One of my first jobs was at The Plant Company where I encountered a woman (my manager) who adored (male) porn magazines, and my first gay friend, Joey, whose family had disowned him for being gay. In the afternoons, he and our manager would lock themselves in her office laughing and commenting on the centerfolds for hours when the store was slow. I tired not to bother them.

For awhile, there was another employee: a quiet woman who drove an apple red Karmann Ghia and would give me rides to the green line—convertible top down. I don’t remember her name but I do remember she was gorgeous in a tough way and always angry. She had an edge about her, though she always took extra care to be gentle with me. Let’s call her Sophie. In hindsight, I doubt she cared for porn or our two managers who spent so much time studying it.

Sophie kept to herself and worked hard. Maybe she was 25—old! I was maybe 14. Once, I met her boyfriend when he picked her up from work. He looked exactly like James Dean in Giant. I thought him the most beautiful man I’d ever laid eyes on. Did becoming a grown-up include a sports car and a gorgeous boyfriend? What a world! I couldn’t wait.

As the months wore on, and spring turned into the heavy heat of July, Sophie blurted out in the middle of a Monday, repotting a ficus benjamina, (a weeping fig) that her previous employer had killed herself. Sophie had previously been employed as a live-in cook/housekeeper, and the beautiful boyfriend had been there, too, working as the family’s car mechanic. “A poet,” she said.

HER KIND

I have gone out, a possessed witch,

haunting the black air, braver at night;

dreaming evil, I have done my hitch

over the plain houses, light by light:

lonely thing, twelve-fingered, out of mind.

A woman like that is not a woman, quite.

I have been her kind.

I have found the warm caves in the woods,

filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves,

closets, silks, innumerable goods;

fixed the suppers for the worms and the elves:

whining, rearranging the disaligned.

A woman like that is misunderstood.

I have been her kind.

I have ridden in your cart, driver,

waved my nude arms at villages going by,

learning the last bright routes, survivor

where your flames still bite my thigh

and my ribs crack where your wheels wind.

A woman like that is not ashamed to die.

I have been her kind.

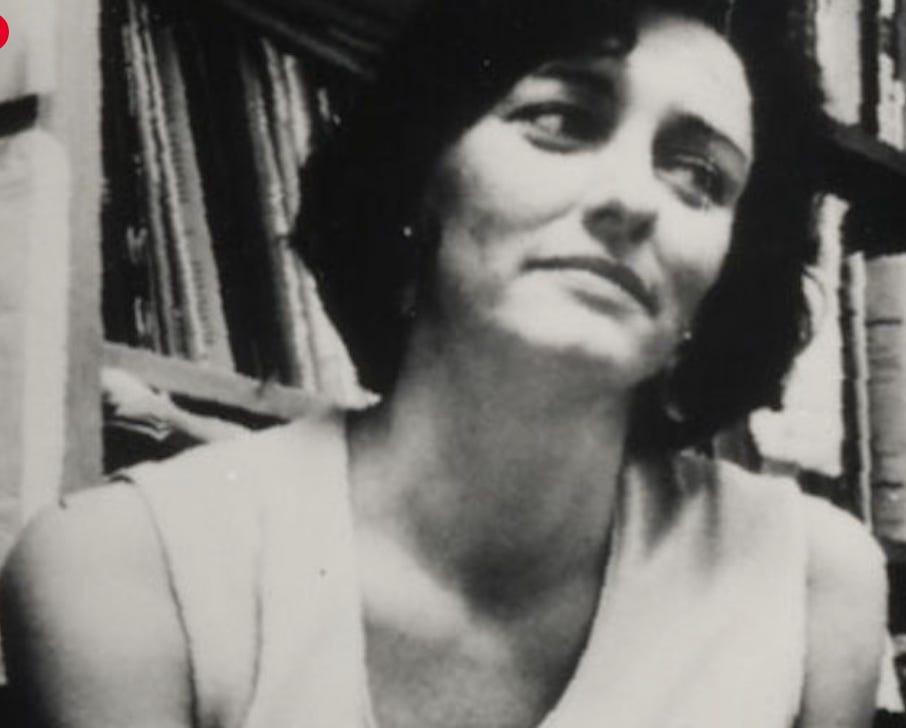

Anne Sexton died on October 4th, 1974 and I met Sophie in the spring of 1975. It wasn’t hard to connect the dots. I so wanted to ask questions about what Sexton was really like, did she like working for her? But the only thing I remember is the anger that poured out of my co-worker. Angry at Sexton for leaving her family, for leaving her.

Sexton’s suicide, coming only 11 years after Sylvia Plath’s, shook the New England poetry world all over again. It was a terrible message to leave to a teenage poet. Did one have to kill herself to be held in high esteem as a woman poet? Did poetry and the hyper tragic go hand-in-hand? Somewhere in the backrooms of The Plant Company, Sophie taught me to reject that pain-filled legacy; to embrace weeping figs and date palms, jade trees and dracena marjinatas. It’s a lesson I hold onto still.